If you find errors OR have additional information about this site, please send a message to contact@waynehistorians.org.

First Baptist Church (cobblestone)

| Historic Site #: | 14-026 (Exists) Type: D1,E1,F2 | Town: | Williamson | ||

| Site Name: | First Baptist Church (cobblestone) | GPS Coordinates: | 43.22469, -77.18055 | ||

| Address: | 4212 Ridge Rd Williamson New York | ||||

| Description: | |||||

| The cobblestone church was built 40 ft. x 46 ft. and laid by members. Site of Williamson anti-slavery meetings and women’s anti-slavery fair, where both African Americans (including Frederick Douglas and Charles L. Remond) and European Americans spoke. | |||||

| 🔊Audio: Tour Sound Bite |

| Historic narrative: | |||||

| Organized in 1821, the congregation built a church with three galleries which burned in 1843. In that same year they began building the current building that was completed and dedicated in May 1846. On June 1, 1973 the building was one of several churches targeted by an arsonist. The cross and bench are among the few furnishings in the sanctuary which were saved. Abolition and anti-slavery movement Significance: The Baptist Church in Williamson illustrates the importance, in Wayne County and across the nation, of grassroots religious support for abolitionism. Because of rapid in-migration from New England, attracted by rich farmlands and easy access to markets via the new Erie Canal, Wayne County had more than its share of local churches who sympathized with reform. In 1843, this church passed an antislavery resolution. Local abolitionists also held meetings in the Williamson Baptist Church, including one that filled the meetinghouse in late February 1848: “Men, women and children, age, youth and beauty, were there,” reported Frederick Douglass, “and all alive in the cause of freedom.” Charles L. Remond, an African American born in Salem, Massachusetts, spoke at this meeting, as did Frederick Douglass, editor of the North Star and perhaps the most famous African American abolitionist in the country, and Giles B. Stebbins, European American abolitionist from Massachusetts. They spoke before “a large and earnest audience.” Remond gave “a most impassioned and eloquent address, designed to show that the Anti-Slavery was the white, as well as the black man's cause..” The second day, the convention met in the Methodist Church in Williamson (no longer standing). In spite of an eighteen-inch snowstorm, the meeting was well attended. At its close, women formed an “Anti-Slavery Sewing Circle, auxiliary to the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society.” Fruits of their labor resulted in an antislavery fair, held on two bitter cold days, with “piercing winds and chilling frosts,” in mid-January 1849. Although the goods were, in the opinion of Frederick Douglass, “too ornamental to meet the ideas of hard-handed, industrious farmers,” the women of Williamson raised $80.00 for the cause. Rochester women “bundled up in coarse garments” and traveled “over rugged hills and icy roads, in open wagons, twenty-six miles,” to help at the fair. Proslavery advocates might think that such behavior was “unwomanly” and “out of her sphere,” noted Douglass, “but Heaven approves, and the slave will bless them.” An antislavery meeting accompanied the fair, and the Baptist Church “was full of earnest listeners.” Griffith Cooper, “that friend of man, the African as well as the Indian,” introduced John S. Jacobs, who with his sister Harriet Jacobs, had escaped from slavery in North Carolina. Jacobs “proceeded in his usual, calm, clear, and yet earnest manner, to expose the system of slavery.” Douglass then addressed the meeting, using “that murderous wretch” President Zachary Taylor to illustrated the “moral state of the nation.” “We were told afterwards,” reported Douglass

that some of the pious voters for this man-stealer and human butcher, thought we displayed an unchristian spirit in our assaults upon the character of General Taylor. This shows how Christians, so-called, may strain at a knat and swallow a camel. They can give the whole sanction of their intelligence, morals and religion, to confer honor upon a slaveholder, slave trader, a bloodhound importer, and a human butcher; and then assume to be discerners of spirits, and very much shocked at anything that looks like an unchristian spirit. Out upon the hypocrites! . . . The time has gone by when such miserable twaddle can have much influence on the minds of men. Douglass thanked several local families for their support of this fair, including John Stretch, who had attended a Western New York Anti-Slavery convention in 1845, subscribed to the National Anti-Slavery Standard in 1847, and was selected at a convention in Marion as one of twenty Wayne County delegates to the Free Soil national convention in Buffalo, New York. I849, he signed a call for a reform convention, to be held in Walworth. In 1850, the federal census listed John Stretch as a farmer in Williamson, with property valued at $7.900.00. Along with many others from Wayne County, John Stretch moved to Adrian, Michigan, before 1867. In September 1849, Douglass spoke in nearby Marion. Rev. Wade, Baptist minister from Williamson, joined him on the platform. Wade told stories about his own experiences traveling in Kentucky, risking his own life on “the mere suspicion that he was an abolitionist.” In Frankfort, Kentucky, he visited Calvin Fairbanks, then in jail for helping people escape from slavery. Wade most likely knew Fairbanks, who had been born in Allegany County, New York, and had visited Williamson at the home of Griffith and Elizabeth Cooper. Wade’s visit to Fairbanks “was sufficient to stir up against him the fury of a mob, consisting of many hundreds, from which he barely escaped with this life.” “Others may tell the horrors of slavery as experienced by the black man,” wrote Douglass, “but it is advantageous to know its cruelties as they are sometimes felt by the white man. - Mr. WADE has it in his power to render the cause of freedom in this region essential service by giving lectures on the subject of slavery; and I earnestly hope he may find it convenient to do so.” Fairbanks spent many years in jail and received the dubious honor of receiving more lashings than any other European American abolitionist. | |||||

Wayne County Historian File Folder “Religion—Churches—Williamson

First Baptist Church of Williamson. Robin Hartley. 1975. Hoffman Foundation Essay

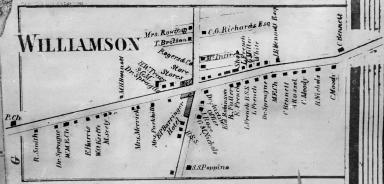

Directory and brief history of the town of Williamson (with map) as compiled by Williamson American Legion Post 394

Uncovering the Underground Railroad, Abolitionism, and African American Life in Wayne County, New York, 1820-1880 pp 369 - 374

Frederick Douglass YouTube Video 1

Frederick Douglass YouTube Video 2

Cobblestone Quest by Rich & Sue Freeman, page 120